"I think that our desire to make history about the present all the time actually kind of robs it of something. We miss the point of just letting a thing be in the past and trying to understand it in the past." Laine Nooney

My rejection of many or most teleological accounts of history as well as singular, continuous narratives in history has never been an easy sell to others; most of the time I keep these particular views to myself. But I can't hide who I am of course and, especially in a back to school season such as the current one, I can't be coy and try and suppress them all of the time.

My abiding immersion into a variety of styles of art has been at least since my adulthood a matter of some purposive deliberation. I do like to reflect in these posts upon the richness of my upbringing in this regard. Initially these experiences of both stage and screen were of course parental decisions.

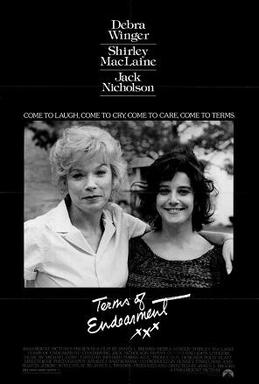

My agency took over though as soon this was possible. One of the curious forms this agency took was a homemade videotape I created consisting of only the scenes of Jack Nicholson and Shirley MacLaine in the film Terms Of Endearment, the antics of Aurora Greenway and astronaut Garrett Breedlove together forming a movie all its own.

I tightly edited their scenes in the picture, concluding around Garrett's line "my stock answer. I love you too kid." This in turn made me the life of the party in that year, since on more than one occasion, people would come over to see this VHS tape I had created.

This period of time coincided exactly with the years I was in college and I remember the playing of this tape was an event in late September or so in 1987. A couple of people were of course unhappy at my violation of the integral whole of the film and were insufficiently amused by Jack Nicholson's behavior for these scenes to be tolerable on their own.

The most pertinent fact about my one, only, and brief foray into doing anything of a technical nature was how deeply I hated it. I hated having to hook up these two machines, I hated the ugliness of all of the materials, and I hated that none of it involved being inside a darkened theatre with other people watching this picture on a big screen.

You could say my aversion to technology started in earnest in 1987.

When you consider, however, that in my first year of college, in 1985, I wrote a required entrance essay that was a critique of the computer itself (and thankfully is now blessedly lost to history) and that the very strength of my essay inspired the faculty to exempt me from having to take freshman English, you could say I have been thinking about these matters for quite a long time indeed.

What I did not know then and has been made abundantly clear to me today - mainly through the extraordinary book by Laine Nooney called The Apple 11 Age: How The Computer Became Personal - was that there was a whole world of people who not only were enamored with these kinds of things that I simply hated to do, but would proceed to make over the entire world according to their tastes. It is important to consider that their world was an incredibly small one. These tech people were forced to forge a compromise with people like myself, and the great majority actually - we who wanted tech things to be immediate, basic and not require you to really do anything. The irony is not lost on me that, being autistic, I would have this one commonality with many in that tech crowd but in most respects I would have had so little in common with them.

My stubborn resistance to anything tech was evidently one trait which placed me in the mainstream of those years. This of course raises the question of how deeply insufficient all of our psychological and scientific categories probably are. I am sure the tech folks resented us and could not comprehend the majority who did not want to have to learn yet another skill for which they had little interest. (This connects to my "hatred" theory of how AI was encouraged to encroach upon so many formerly human works and behaviors).

A lot of the history of the past fifty years could be read as a struggle between these two groups, and I suspect a lot of the enormous financial gain of some of these tech folks ws and is a kind of revenge on their part against the masses who didn't get it - the joy and beauty (from their point of view) of engineering and tech. This particular narrative always reminds me of the Alan Cumming character of Sandy Fink in Romy And Michelle's High School Reunion: the science whiz who was bullied in high school but ends getting back by getting rich and famous. You might say I must have loved those scenes between Jack Nicholson and Shirley MacLaine so much that I had to do something I hated to freeze those scenes in time for repeated viewing! For me the whole question of artistic objects like films are inextricable from the question of mass tastes and preferences more generally - including the platforms and means with each any of us experience any art object.

Mitch's selection of images from the film

As Nooney expresses so beautifully in their book:

"A tremendous amount of social and financial effort went into naturalizing and normalizing the notion of a computer of one's own. It was not simply that users had to reimagine these technologies in order to make them practical or useful, though examples of such behavior abounds in the era. It was that personal computing emerged wedded to an affective imagination that sutured individual creativity, discovery and opportunism to a sensation of national rejuvenation via technological innovation. This is the source of the electric energy and earnest capital reinvestment that kept the consumer micro computing industry afloat, no matter how many times it was proved that mass consumer interest was tenuous, uncertain, or sometimes not there at all. It is in the hope of the thing that might come that every time personal computing failed, it was forgiven and allowed to try again - until computing's embeddedness in our world did become a forgone conclusion." My affection and immersion in various styles of art will never lessen nor vanish. You could say then that for me art itself, as well the diversity of art might be what electronics, making ham radios and coding are for the tech folks who took over our world. My estimation for James Brooks only grows over the decades; I consider him so good in fact that I would place him in the company of an Edward Albee or a Harold Pinter. Yet he is but one kind of filmmaker and writer. I recently watched a movie, Showing Up, that is just as unique as Brooks, while completely different to anything written by Brooks in about every way you could imagine a dramatic story with characters could be. What makes Reichardt's writing valuable is that the picture is as much about what is absent as what is present on the screen. I can imagine with considerable fullness another kind of Showing Up, one that I would bet my bottom dollar would have been more congenial to and celebrated by those who were not its biggest fans. The main character has no love interest, neither husband or same sex partner. There are no scenes of Birkenstock shoe leather as she fights for her first show, a la the Melanie Mayron character in Girlfriends.

Indeed she is already an established artist, deeply immersed in an artistic community that long predates the film's beginning.The first major conversation, by phone, with her dad, is conspicuously missing the kind of heated emotion that many of us have been conditioned to expect in scenes between adult children and their parents. (And we are not even speaking of how the scene is shot).

One significant relationship with another female artist consists of them fighting over the lack of hot water in the house in which they live, and the prospects of this crucial bit of living infrastructure being fixed. A pigeon is a major character. Kelly Reichardt has a deeply ascetic and concentrated conception of eventfulness and drama. There are as many events in her picture as in Terms Of Endearment actually, but we are not in the habit of registering what happens in the former as anything like an event.

Showing Up could just as well been titled Paying Attention, but she is too savvy and subtle a filmmaker to have done that. Now I will not go so far as to say that these features make Showing Up superior than more familiar types of drama; but they do redirect our attention in such a way as to embody in itself a kind of education for the audience and it does strike me that this rarity is in itself a kind of virtue. I am aware that this preference on my part reflects my preference for a certain kind of quotidian humanism, a taste not shared by everybody. It is also reflects my bias in favor of the comic too. The comic, among many other virtues, is decidedly anti-apocalyptic.

All of us have preferences and because we all find ourselves creatures of one time or another, there will be dominant and dominating preferences that happen to cover a particular era. Style is the decisive matter.

A lot of what goes into a style being what it is is a strong precedence for what audiences have accepted to desired in there past, or for some kind of tradition: an audience actually anticipate or expects certain kinds of styles. These preferences, whether conscious or not, form a symbiotic relationship with what can be found in a given society at a given time. Terms Of Endearment and Showing Up are both movies in very given and particular styles and those style comprise the largest part of why and how they make us feel the way they do.

I like to quote GeorgeTrowe when he says at the end of his book, My Pilgrim's Progress, quoting somebody else, "'Well you can't help who you love.'"

I suspect this applies even more so to what as to who. All I can do in posts like this is direct attention to this or that what in the world, if only because I think it matters. That might not be much but I do like to think that it is something.