Of Things Great and Small, Outer and Inner

- lauriesstorygarden

- Nov 1, 2023

- 9 min read

What is the relationship between grand exterior events and the discrete, interior things I or we can call art?

Or, rather, to be fair to my own pluralism, what are the relationships between these?

Any answers given will necessarily be based on what the various meanings that artworks hold for both individuals and larger associations of people, including, I am sad to report, the unthinking or ill considered notion that there is not much meaning or consequence to an art work at all. This last mistake is second in prominence only to the notion that art exists exists chiefly as a kind of solution or goal in society itself, as it is is imply another part of “real life" - perhaps this last being the dominant viewpoint today.

I will offer here two examples of aesthetic objects or artworks that entered my nervous system rather early, thus forming who I am today.

These are meant to be snapshots - both in the sense of time capsules of moments from the past as entire eras unto themselves, as well as representations in current memory of art objects from a certain time period that has now passed.

The first example is the first recorded jazz music I think I ever heard, as well as the first music I ever heard from from Miles Davis.

Interestingly this was not a more canonical work of Miles Davis, the leading one perhaps being Kind Of Blue, but this Fontana album of Davis’ score for the 1958 Louis Malle film Ascenseur pour l’échafaud.

I first encountered this album from my father’s record collection sometime in the middle 1970s and the main aesthetic quality that hit my being was the sound of Davis trumpet, in particular the first few measures and phrases of the cut titled Generique. What I would say now but at the time as an eight or nine year boy was not quite so articulate with linguistic description and response to the world is the central was the beauty and eloquence of the horn, second only to the minor mode and sound of the famous French players.

Today I could talk about its sensuality, its richness and its sublimity. Yet it is amazing for me to consider that I would not be able to witness the black and white noir spectacle of the film’s heroine, Jeanne Moreau as she walked down city streets of Paris, in the same film until 1987, when I was able to finally see the film and write about it.

Here is an emblematic clip:

Now to pull back into the outer world, there was this larger social era of Post War France and Paris, of coffee houses, and ideas like existentialism, and Jean Paul Sartre and Simone De Beauvoir, of the trauma of the occupation, the partly healing release of French fifties artistic culture, and the embrace of Miles Davis’ music by Europe more generally. Then there is the special person of Miles Davis himself, the fact of his being from Illinois with a father who was a dentist, or having attended Julliard, amazingly all the while creating the new language of Bebop at the very same time with colleagues like Charlie Parker - itself made possible only by the power and influence of New York City itself.

There is his long journey through many jazz styles, some of which he in part invented himself, and even some of which were in 1958 far from being existent.

And, not necessarily lesser in important in an objective sense, there is the reception of audiences to all these stations of Davis’ journey. For example, the fact that so many musicians and fans alike had told me, ad nauseam, in the 1980s through the 90s, that the “best” period of Miles Davis was surely the period of the very years of the late fifties to middle sixties. And naturally I felt I had to keep to myself from interlocutors that my favorite Miles Davis was the album Filles De Kilimanjaro, which was a few years later.

As you might hear it is so similar and so very different from the French score.

It is even more curious too to consider that my favorite trumpeter of all time remains Freddie Hubbard, mainly for the character of his improvised line (though Freddie’s tone is also incredible). Such preferences are natural to the story of all art as they determine so many matters, from what gets to be actually funded, to what gets lost or neglected, sometimes quite willfully. This is a matter of attention: the artist wants to depict, discuss this and not that and no matter how inclusive or "holistic" any artist considers what they are doing some kind of choice or (de)emphasis is always operative - even if it is as simple as the decision to play a very slow, impressionistic ballad with rhythm and blues figures immersed within it.

Now somehow all of these matters, which might feel comprehensive from the length of my listing but surely leave some important facts out, could be said to go into “making” the sound of Miles Davis’ music and tone of his horn with which I fell in love.

Yet, as with all artistic presentation to the public, one might not necessarily know about any of the background details nor very well be thinking of any of it when encountering, in this case, instrumental music. I feel there is very much a gap or tension between the outer facts, which we often feel or deem to be causal, and inner feeling or experience.

As humans we can be moved by seeing Jeanne Moreau in the film walking and thinking to herself while hearing the Miles Davis music and this sense of being moved is most important. I don’t want to say it is all important but it is the heart of the word aesthetics as a noun.

Around the same years that I first heard this Miles Davis score I also saw a production of Bob Fosse’s Chicago, in fact the original cast production!

Although I think about the musical Chicago and Bob Fosse fairly regularly in my life in the very early years of YouTube somebody posted the following video that it raw and original footage of the show in 1974.

Seeing this archival material and remembering undergoing the feeling of seeing Chita Rivera and Gwen Verdon on the stage as a boy saw a further flowering when I came across a Mike Douglas Show episode with both women - up close and personal - doing publicly for the show. (I am having to include this in three parts since given the age of the upload on YouTube, have not yet been uploaded in the entirety they appeared on television in the 1970s.)

Bob Fosse himself has the deepest roots in the 1950s era. Here is a supreme example of his own work in those years, his genius as a dancer one part of the complex artist that we was to become.

This is from Richard Quine’s My Sister Eileen:

Indeed, I should say that one thing that makes Bob Fosse so good is his honoring of his own ambivalence about "show business" and entertainment, his criticism and appreciation for some of the same things, that life is not nor has ever been all bad or all good, though in fairness in may times the ratio of the two has been inhospitable. This through line goes all the way through his work, concluding with Star 80.

If he were an artist that either simply celebrated or flattered our love for traditional entertainments on the one hand, or simply attacked them in the manner of an Avant Gardist or Leftist on the other, he would never have been the innovative and important artist that he was (though possibly would be even more celebrated in today's era than he is).

Here are two fifties record covers that are in my possession featuring Gwen Verdon in their production of Damn Yankees.

I presume RCA Victor wanted customer choice of how they wanted to see the show represented.

There is so much I would want to say about Bob Fosse but I will restrict my comments to the revolutionary aspect of his artistic innovation. Among many other things he was rebelling against the dominant Rodgers and Hammerstein family values and sentiment as well as the liberal and progressive values of productions like South Pacific and Carousel etc.

He was interested in aspects of life that were more urban and more adult perhaps and music and dance that in turn reflected these interests. As a boy I was most taken with these two women and considered them infinitely enchanting.

Though these are the inner aspects of my reception of artistic practice and performance there were a great many outer matters I could not have possibly known at the time, for example that both women had already had long careers before the 1970s or that many of the things they were doing in this show were influenced by artistic movements like vaudeville and/or burlesque - things about which I knew next to nothing, in the same way I did not know much about Miles Davis’ life story nor the importance of Minton’s Playhouse in the story of the formation of Bebop Jazz.

Instead I was responding to the immediate sensation of Chita Rivera and Gwen Verdon as performers and all the artistic decision making of Fosse’s and their’s choreography.

Equally important are the creations of John Kander and Fred Ebb and the particular musical and poetic language they used to create the stylization of the show. Until my middle adolescence the famed ubiquitous poster of this original production hung in my bedroom in a way not unlike a poster of Farrah Fawcett Majors or Cheryl Tiegs at roughly the same time.

It would be some decades too since I was able to see projected open the big screen the musical film Roxie Hart with no less than Ginger Rogers - itself based on a play from 1926 by Maurine Falls Watkins. And it is simply remarkable to think that so many years later - as recently as 2019 - the lives of Gwen Verdon and Bob Fosse would be dramatized by Michelle Williams and Sam Rockwell in the series Fosse/Verdon.

In a costume/historical work like this of course great attempt is always made to include both of what I am calling the outer and inner in various ways. (As well as the attempt to take seriously all kinds of “snapshots”) Of course for me the excitement and frankly, joy, at seeing this culmination of a long line of so many artistic projects over the decades is itself something to behold, and is its own matter of consideration, alongside the achievement of both Rockwell and Williams as performers.

And finally there is the motley mosaic of all of this disparate artistic forms - commercial Broadway musicals. Tin Pan Alley songwriting, popular dance styles, Hollywood musical practice in the 1950s, 1970s artistic culture in general, the history of the 1920s and 30s, the Great Depression, the Jazz Age, and so much more.

All of these are grand, “outer directed” phenomena yet can be crafted aesthetically into “inner directed" works of art.

I wonder if this is the same as how I learned to play a certain kind of piano and in doing so had to learn something of all of the achievements of pianists from other eras long before the one in which I found myself?

Earlier I described one way of understanding Bob Fosse was that he was responding against a certain kind of musical of the fifties, say, the Rodgers and Hammerstein work of the 1940s and 50s.

This of course does a partial disservice to the Rodgers/Hammerstein style - while at the same time reflecting some truth in that same style. I actually love some of Rodgers and Hammerstein, but I love Bob Fosse even more. Or you could say that I like and respect the former, but embrace and feel some kind of unity with the latter, if that makes any sense.

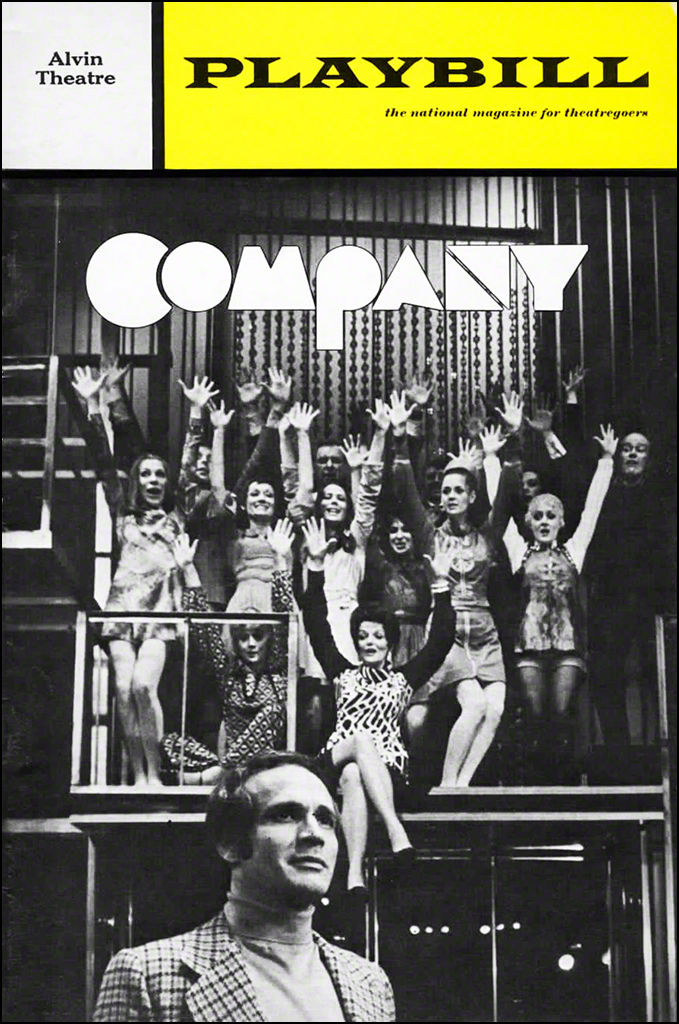

Works of art can be many things at once, just as they can choose to embody a single aspect of life. And as audiences and creators we are inevitable going to prefer some of these over others. There is an amusing scene early in Fosse/Verdon wherein, at a cocktail party in celebration of Fosse’s latest smash hit Sweet Charity, the Bob Fosse character reacts negatively to hearing from his friend Hal Prince that Prince is excited to be “working on Steve’s new musical about a single guy who can’t hold down a relationship. His married friends all want him to get married even tough they’re all miserable.” And Fosse reacts with sarcastic derision ‘I’m on the edge of my seat.”

Or rather, he knew that the kind of serious and adult material he wanted to focus on in his own work did not extend to the kind deployed in Company, even as we might really that there is a little Fosse in terms of subject matter in Company. (Company is “about” the sexual revolution, a Fosse topic if anything is). And it is useful to remember that Oscar Hammerstein was Stephen Sondheim’s mentor and teacher.

In keeping with my own sensibilities I feel it always best to focus on particular artworks and artists from time to time, not really in order to offer any kind of definitive summary of them or even to describe why I like them - when I do. It is really to put the spotlight on the aesthetic, which is thoroughly embedded in how all of us relate to the arts and letters.

And, to hopefully not be too polemical or tendentious, I feel I am living in an age in which what I would call Sociology is always threatening to replace Aesthetics, and I am defining Sociology here in a broader sense than is usually the case - to include all sorts of practices from censorial regulation, ethical or moral evaluation, the disciplines of history, psychology, biography, media and communication studies and the daily news cycle. I don't want us to lose the feeling of hearing Miles Davis' or Freddie Hubbard's horns or seeing Chita Rivera and Gwen Verdon on stage or screen. And, though much more can be said about these admittedly particular examples, it as humans with inner lives that they come to mean anything to us at all.

In an age of so-called artificial intelligence these last assertions of mine might, in the fullness of time emerge to be more important than we now realize.

Beautiful writing, thank you!