Diversity, Beliefs, Democracy and Art

- Mitch Hampton

- Jul 1, 2023

- 10 min read

"I should make my own position as a philosopher clear. I'm not a relativist and I'm not an absolutist in the senses I have been talking about here.

I am a fallibilist. And that means something like this: a fallibilist is someone who passionately believes certain thing.

Passionately believes certain things, some of them quite bizarre as you will find as we go along. But about those beliefs I believe that they could be wrong. A peculiarly modern attitude but one that I find myself forced too - through long and bitter experience - not only philosophical by the way - but historical in a more bloody and mundane sense, it seems only wise policy both phllosophically and politically to be able to hold a belief passionately but to have a belief about that belief that it could be wrong.

Some of you may think that is absolutely paradoxical - that if one must believe something passionately that you gotta just believe it. And I hope that turns out to be wrong because it doesn't seem to make me feel any more schizophrenic than the rest of you to both know that I hold a series of beliefs quite deeply and yet to have a belief about them at another order that they could be wrong. In any case that's not a bad characterization of the position of fallibilism. And I'm a fallibilist about fallibilism! Which means that whole stance could be wrong.

So I'm a fallibilist all the way down." Rick Roderick, in 1992, for The Teaching Company." July of course is most famous in the United States as a commemoration of the founding of our particular (and peculiar) country. This being an arts podcast and me being a person unusually lukewarm to the political in general, while having spent a good part of my adult life feeling otherwise and involved in political activism - activity that I frankly abandoned beginning at the turn of the 21st century and even further distance under the circumstances and climate that began in the years 2015 and 2016, and under which we are still greatly suffering.

I thought it might be interesting to speak in a direct while still philosophical manner about what I, for lack of a better formulation, continue to "believe".

Like the late Rick Roderick, whose very lecture reproduced here so many years later and to which I listened when they were released in 1991 or so, I too am a fallibilist. But of course there are many additional components to my self that one could place into some kind of category, like improvising pianist and podcaster. If you look at the included photos below, as early as the agent of 13 and 14, I loved movies so much that I was a subscriber to American Film magazine.

I was also subscribing to Contemporary Keyboard and Downbeat magazines as well. But I have few remaining copies of these, unfortunately.

You might be surprised to see that as a teenage I found myself in an 1985 issue of Downbeat.

So you could say that my love for music and movies goes pretty deep.

Now of course you can say that those two fields are both part of the wider performing arts, but it is always a good exercise to step back and imagine or wonder about all the many things humans are interested in, whether valuable to a majority or not. I suspect if you pull back and look at this wider picture you might be in awe of the sheer diversity of human life and culture. I mentioned that I have multiple identities that can be described in terms of categories - as crude and partial as these are. One category might be more important than these, and there are some facets I have not even gotten into explicitly in posts like these, and that is I am a pluralist. Like so many matters in life these concern the "imaginative center", a phrase that serves as a synonym for what is most important to any of us. I should emphasize in what follows that I do not use the word values in the way they are ordinarily described in common conversation - as synonyms for one's morals overall or what is good. I use the word in a descriptive sense for what one might care or not care about. This will hopefully be clear by the post's conclusion.

I am unable to think and feel in an unphilosophical way, so I do beg your patience. As I said, I am a pluralist. In particular I am a values pluralist.

I mean this in the double sense that values themselves as I understand them do not form a unitary whole and that they are multiple, also there is the inevitable and intractable fact that different people, by virtue of simply showing up, will prefer one or more values than others, in keeping with the immense power of human preferences, both individual and collective. (Collective preferences inevitably creating divisions or at the very least separations inside of society).

Long before I ever encountered Sir Isaiah Berlin the chief "exponent" of pluralism in the modern era, I think I first encountered the concept in William James' A Pluralistic Universe.

This is far from the place to get into that particular text from 1909. I have written and spoken about Isaiah Berlin before on this podcast. I found the Stanford Encyclopedia entry on pluralism rather good especially as a kind of summary for those of us who are admittedly are not as into this stuff as I am.

"Several values may be equally correct and fundamental yet in conflict with one another".https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/value-pluralism/.

Isaiah Berlin's favorite word for this phenomenon was "incommensurability".

Lest you think all of this is only an abstract matter that derives from my love for such philosophizing, it actually has the deepest roots in my own life, starting from at least early childhood.

It involved above all negotiating a world that was not only objectively at odds with me because of my own autism, even if I was not aware and knowledgeable at that early time of this reason. (The world being essentially designed for other kinds of psychological types and note that I say the plural "types".

People in the statistical majority are themselves unique, of plural kinds while still being united in being non-autistic - one of my problems with the choice of the neologism "neurotypical" that is now in fashion). But pluralism forms the very heart of our podcast: my love not only for the arts themselves but love for many arts that in many or most respects are internally separated by style and sensibility, such that they can be said to encompass differing world views.

Growing up and throughout my life, I also noticed that both the fans and consumers of these various arts seemed to occupy different worlds, and this in an era not notable for its polarization and structured by the artificial consensus of the twentieth century, of Walter Cronkite and Johnny Carson. Of course many kinds of people enjoy more than one type of art. People will enjoy both comedies and tragedies; and there are those who like both classical and popular music. As a young teen I was already subscribing to American Film Magazine. I noticed that within the same issue there would be an interview with actor Jack Lemmon as well on the great filmmaker Luis Bunuel.

Now there is little or close to nothing in common between the films in which Jack Lemmon appeared like Avanti,The Front Page, or even Save The Tiger and the films made by Bunuel like The Discreet Charm of The Bourgeoisie or The Milky Way.

It IS interesting that both Jack Lemmon and Catherine Deneve were in the. film The April Fools together (one of the lost gems of the 1970s) and Bunuel did cast Deneuve in his famous film Belle De Jour. But I can't for the life of me think of a single film in which Jack Lemmon appeared that had much in common with Belle De Jour. And that is only within one art form, movies.

I also noticed profound differences between the world of classical music and the jazz musicians with whom I had begun to work and play. Thus there were differences too in the two cultures as well as in the music created, sometimes differences in how music can be said to be defined.

One of the things I really appreciate about the movie Tar is that it brought out with some accuracy a sense of the strangeness of the classical music world itself - in ways rarely or even never discussed in mainstream filmmaking. (And by this I don't even mean the fictional title character or this or that event in the picture but the overall milieu; I also mean something more specific than the notions of either ambition or "excellence" themselves).

Now pluralism can be seen as an empirical truth about how the world or at least the social and cultural world actually is. Commentators often say that we should look first for some universality or some commonality, stuff thought to naturally bring us together, to solve our problems.

What if instead - as we pluralists would suggest - start with a presumption of difference rather than commonality, and moreover give up our desires to push for sameness?

To be most blunt about it, to give up our belief that our particular lifestyle or set of core values can or should be replicated by others? Of course to make this extra step means that one has to hold all of their internal stuff like convictions a little more lightly and certainly not dogmatically. The problem as I see it is a constant and unconscious commitment on the part of people to advocate for their particular vision of life and consequently to want to impose that vision - whatever it happens to be - upon others as something objective or thought to be objective.

Indeed I am going to be as least coy as is possible and state that practically all of our problems today, including our most disturbing one of political violence (as well as individual, "mental health" related violence) stem from this clinging to or craving for a singular objectivity, which is only the most apparent in all forms of conservatism but not only a problem there. Writing at the conclusion of his book The Nineties, Chuck Klosterman chooses a particular phrase that I think represents the world that has been created, whether we call it the Internet Age or any other label: "There's a long standing belief that national trauma shatters the existing status quo and splinters the interconnectivity that creates a phantasm of security. What happened to North America after the eleventh of September was the inverse of that. Society did not, in any way, disintegrate. Instead it was irrevocably jammed together. Every conversation became the same conversation. Ideological differences were inflamed, but not because of intellectual separation. It was the narcissism of small differences, amplified into differences that were no longer small. The phantasm that got shattered was the possibility of living an autonomous life, separate from the lives of others." I find it most interesting that Klosterman is targeting the events of Sept 11 as the real impetus for our current sorry state and implying that the internet and social media is more an effect of this initial terrorist Event. The phrase "jammed together" is a good one; it implies ill consideration and force, a society where people and things are jammed together seems like one in which space and separation are willfully ignored, as if they were not as much needs as proximity and closeness.

Even if it stems from an understandable and venerable belief in the unity and interconnection of the world, it is still a problem to simply assume that the world of today as it was engineered will simply produce good, and it strikes me as having been reckless, to put it mildly, to base an entire social system, through technology, on these assumptions. But maybe it was all a massive overcorrection to so many hundreds or thousands of years of exclusion and excessive separation.

This is intimately connected to the concept of pluralism for the simple reason that, as I would remind anybody who cares to discuss it, our differences and our status as plural creatures makes any such project of "singularity" a problem from the beginning.

Now I have no idea if Klosterman's account of our contemporary period is throughly accurate, that is, in all its details. But it strikes me as better than a more technologically determinist account, one wherein we become wholly different people according to our tools. Rather, it is relations of people - between nations, between and among people within nations and things like nations, wars, and terrorism that precede inanimate machinery, however ubiquitous the machinery.

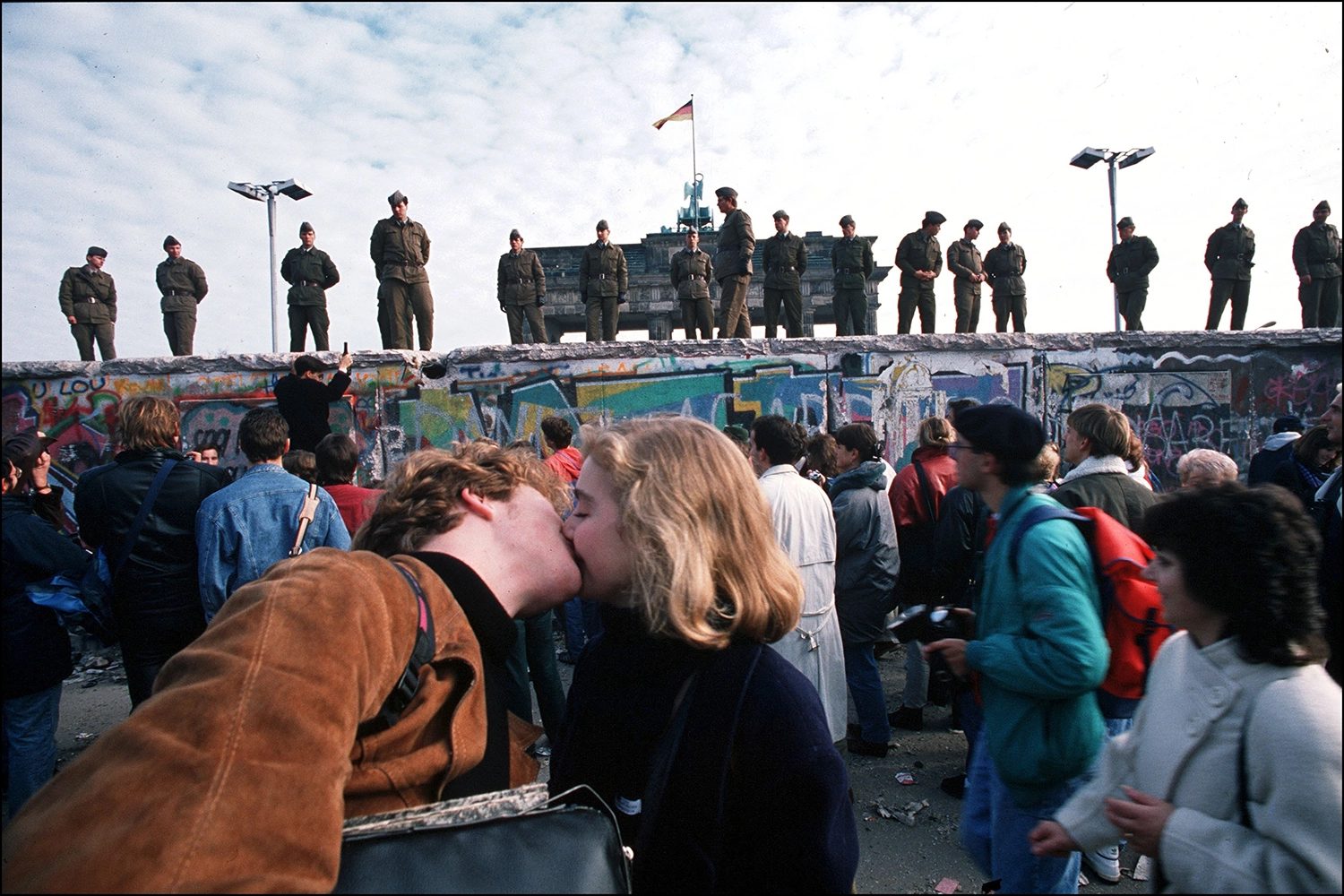

For Chuck Klosterman it was events like the Fall of the Berlin Wall and 9/11, and I would add the tragic destruction and loss of the truly great and hopeful Tiananmen Square revolt in China of 1989, that single defeat being a great source of many of our current woes.

These remarks will present the limit of how much I want to say on such matters in this space.

We have, or attempt to have, a liberal democracy precisely because it is the only structure that can serve our natures as plural creatures. Many might not formulate it as such or might see democracy as some kind of prior, ethical foundation but to me this gets things backwards. Our pluralism is the reason for it as a preference to tyranny. (It is also why Democracy breaks so many hearts, those hearts that do want to instruct others how to live. It is precisely the purpose of a liberal democracy to not tell you what to think, how to live or what to do with your body. This is what most who do hate democracy - and it is far more than we might think - hate about it.)

As human beings we were always plural though in the main societies did their best to counteract or ignore this fact, usually through some kind of hierarchy, a monarchy, or one artificial consensus or another.

When I discuss pluralism it is no different from our decision on this podcast to discuss as chamber wind instrument work dedicated to the victims of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal church shooting in 2015 and a romantic comedy about dating in 1984 in the same platform. It is sensible to ask about the way in which we share a world.

Here is one.

As David Hart says in a concise statement that perhaps speaks best to the need and reality of some kind of unity:

"Mind, life, and language are all one and the same, and are all manifestations of one and the same irreducible reality - which is the ground of all other realities."

And it is in this one sense, you can say, that Art and Life are one.

Comments